Politics is not dispassionate, it never will be. Emotion seeps through, however, how can we tell one emotion from another? You cannot necessarily ask the population, as a generalised group, how it feels… polls like that would suffer from a requirement that the subjects be conscious of their feelings.

The biggest difficulty for me, as conversations today have proven, is demonstrating that there is a fear or insecurity separate or linked to political anger. I have four cases in mind: 9/11, the internment of Japanese-Americans after Pearl Harbor, the abduction issue, North Korea in Japan, and China in Japan.

9/11

The tragedy that was 9/11 was, to my mind, the catalyst for heightened anger and fear in American politics (global politics even). The anger is perhaps the most visible element: the intervention into Afghanistan and the outcries of defiance following the attacks. Anger is a normal and healthy response.

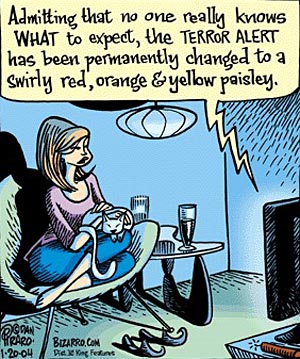

However, it was also accompanied by an underlying sense of fear which could be tweaked and activated by way of the media. Consider the countless news reports of ‘terrorists’ being arrested in the US and UK. Each report was unlikely to be given a follow-up, despite the fact that a large number of these arrests resulted in no charges. The talk of a possible dirty bomb threat was possibly one of the worst instances of fearmongering post-9/11, particularly when you consider the complete lack of evidence behind the reports.

With these two elements at play, it is difficult to determine which is at work in certain events. Is legislation such as the PATRIOT Act guided by fear of repeat attacks, anger against what has already happened, or (more likely) a mix of both?

Japanese-American Internment

I think that one area where fear is more clearly at play, relative to anger, is in the internment of Japanese-Americans following the attack on Pearl Harbor. They were clearly victims of a fear of fifth-columnism that targeted an entire national/ethnic group. American citizens were deprived of their liberties, showing how fear might overturn the everyday foundations of civil and political soceity to create a state of exception.

The fear was exacerbated by the xenophobic tendencies of the majority at that time. This fear operated societally and governmentally (leading to Executive Order 9066, the instigating order). There was a clear polarisation of ‘us’ and ‘them’ in both domestic and international contexts. While, anger clearly played a role in the military campaigns against the Japanese, it was in the domestic context that fear played its part.

Abduction Issue

Now to the issue I most concern myself with, the political fallout over North Korea’s abductions of Japanese citizens in the 1970s and 80s. It is my belief that there is only one major emotion at play here: rage. Despite the title of the blog, I do not believe that the abduction issue has incited fear in Japanese society or politics. I don’t think many people believe that North Korea is still abducting Japanese, nor do many wonder if it could happen to them…

North Korea

… however, I do believe that the threat image of North Korea, more generally, generates fear in Japan. This was the topic of the conversation that generated this post. My friend believes that there is very little fear about North Korea in Japan, and even then, the level of fear received its biggest boost in October 2006 following the nuclear test. I don’t yet know whether I agree or disagree.

In one sense, I disagree because it seems to me that something about the population’s attitude to North Korea is being preyed upon by the Japanese leadership. Here is another problem for researchers: one will find it difficult to find fear in any other sense than retroactive inference. In one paper I read during my research, “Fear No More: Emotion and World Politics” by Emma Hutchison and Roland Bleiker (forthcoming in Review of International Relations), the authors critique the social scientific method as being unsuitable for studying fear, praising, instead, an arts and humanities approach. Certainly, the different standards of inference and logic between the two disciplines makes the choice considerable.

However, at the same time as I disagree, I also do not. When I state that there is a politics of fear in Japan regarding North Korea, I am not presupposing a great deal of fear. Instead I am suggesting that there is a background level of insecurity which is being tapped by the leadership in order to promote certain policies and push certain ideological beliefs. That does no require a large amount of fear, just enough to allow it to be tweaked.

It is also in this case that we might see a possible difference between anger and fear in politics. It might be the case that anger is short-lived (encouraging strong and immediate reactions to events, such as through the imposition of sanctions) whereas fear is continuing (the Taepodong shock in 1998, for instance, exposed the real threat posed by North Korean missiles, one which certainly still exists).

China

Having denied the significance of fear regarding North Korea, my friend then suggested that it was China that generated the most, primarily because it posed a powerful threat. Again, I just cannot be sure at this stage whether I agree or disagree. For me, the crucial issue is that fear of China is not, at this stage, self-justifying. It seems as the elements of the government have chosen to concentrate on the fear generated by the North Korean threat in order to prepare for an eventual confrontation with China. It is the North Korean missile threat that has made Japan more determined to pursue the Theatre Missile Defence system, for instance, and it was North Korea’s intelligence activities in Japanese waters that led to decreased restraints on the use of force by the Japanese Coast Guard. Both are applicable to China, and thus tackling the North Korean threat goes some way towards confronting China.

Conclusion

As it stands all that I am left with is questions. Clearly I need to work on my definitions of fear, and attempt to unpick the links with other emotions. At the same time, I need to work around the limitations posed by the study of said emotions. Finally, I need to conduct some primary research to gauge the threat perceptions and anxieties of the average Japanese citizen. All of this will take time and effort, and I hope this forum will provide an outlet for my energy.