This post will be a reader on the Burakumin, the underclass of Japanese society. It unfolds a lot like the Wikipedia article on the subject, but I assure you, I came to it independently! I will begin by discussing who and what are the Burakumin. I will then examine the discrimination against them, past and present. I will end by discussing the traps of the modern society in which they find themselves, and then discuss the hopes for the future. A lot is written about the Japanese and their attitudes towards foreigners and their claims to homogeneity. However, we often forget to consider that there are even those ethnically, politically and culturally Japanese who are discriminated because of their birth. Like returnees, the Burakumin are from the inside, looking in (to steal Fukumimi‘s by-line).

Terminology

There are many terms used to describe the Burakumin. The term burakumin (部落民) means people (min, 民) of the village/hamlet/community (buraku, 部落). However, min is normally combined with other kanji, such as with kokumin (国民) which means people or citizens. In this case, min comes from juumin (住民) which means residents/inhabitants/citizens, and so sometimes you will see them labelled burakujuumin. In Japanese, burakumin is quite blunt, it is typically used in conjunction with hisabetsu creating hisabetsu burakumin (被差別部落民), ‘people of the discriminated community’. This is the more politically correct label, but for the sake of brevity, I will use burakumin. Politically, often the term dowa (douwa, 同和) is used. It refers to assimilation and equality. Finally, the burakumin have sometimes to referred to themselves as mura no mono (村の者) which means the same as burakumin, only without the negative attachments of buraku.

Origins

The start of the Edo period/Tokugawa Era (1603-1867) brought an increased awareness of social status. Social mobility was hampered by the Edict Restricting Change of Status and Residence (it has many names, perhaps more commonly called the Separation Edict) ordered by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in 1591. This was a law that prohibited class mobility, forbidding farmers could not train to be warriors, for instance. Ostensibly, this was to establish a stable agricultural labour force to support Japan’s coming invasion of Korea (1592). However, it was also likely that he was attempting to consolidate his power (at that point, regent to the Emperor) by forbidding the rampant mobility of the Warring States period (sengoku jidai, 戦国時代), a fact also in evidence in the 1588 ‘Sword Hunt‘ (in which Hideyoshi’s forces confiscated the weaponry of rival factions) and 1590 ‘Expulsion Edict‘ (which sought to expel newcomers from villages, particularly to stop masterless samurai (rounin, 浪人). The edict of 1591 legally and systematically fixed the structured society that was to dominate the Edo Period.

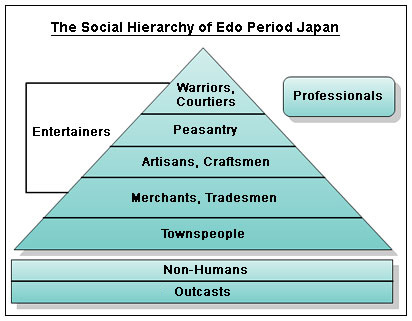

There were several classes and castes in Japan. The system was referred to as shinōkōshō (士農工商). The upper rungs of society were filled by the members of the imperial family and the warrior (shi, 士) classes. Under them were the peasantry (nou, 農), the people who worked the fields, comprising the majority of Japanese society, as you might imagine. Because they fed the population, they held a higher rank to the artisans and craftsmen (kou, 工), and they in turn held a higher social rank than the merchants and tradesmen (shou, 商), who were deemed to be of little value to society despite, or perhaps because of their riches. Townspeople, of most other varieties, were at the bottom of the social hierarchy, unproductive and not serving anyone, they were of little value to lawmakers.

There are some more nebulous classes. Entertainers have strong links to the societal elite, but because they tend to the merchants (the only other group who can afford their services) they are difficult to place. They were placed under firm controls by the shogunate and their ranks included even the highest courtesans and geisha. Similarly, the professional class of doctors and priests, for instance, were subject to strict controls and were theoretically apart from the classes.

However, there were two groups of untouchables, the lowest of the low. The non-humans (hinin, 非人) were the victims of the last remnants of social mobility. They were registered beggars, essentially ex-convicts, prostitutes and vagrants. However, even these people had slightly more privilege than the outcasts (eta, 穢多, ‘abundance of filth’). This group was hereditary, composed of people who slaughtered animals and dead humans. They often called themselves kawata (‘leather-workers’) which was one of the principle occupations of the eta. Their taint (kegare, 穢れ) comes from the Shinto belief that working with the unclean brings a person further from godliness, a matter made more taboo by Buddhist tenets against killing. It is the eta who the modern-day burakumin hail from.

The eta had been an important group during sengoku jidai, when the continual fighting demanded leather for armour. The unification and peace that followed Hideyoshi and Tokugawa meant that this fortune did not last. The development encouraged to foster good relations with the kawata ended and they were ostracised, subject to discrimination that found its roots way back in the Heian period (795-1192).

Discrimination: Past

The eta were segregated from Japanese society. They were given their own temples and prohibited from visiting other religious sites. While Buddhists were given kaimyou (戒名, ‘regulation name’), two-character posthumous names sold by temples by the character, eta were only able to receive derogatory characters such as ‘beast’ and ‘ignoble’. They were not allowed to tend to paddy fields and could often be found on the banks of dried-up rivers. Discriminatory legislation was largely decentralised but were varied in nature: restrictions on clothing, hairstyles and footwear, and prohibiting eta from entering towns at night, having windows facing the street, buying land, and entering the homes of peasants.

In 1871, the Meiji government declared the Emancipation Edict (kaihourei, 解放例) which incorporated the eta–hinin into Japanese society. This removed their monopoly on the ethically undesirable jobs but by no means reduced the discrimination inherent in societal opinion of the workers of such jobs, and so they benefited little in practical terms. The eta, by now known as burakumin after the designation of their ‘ghettos’ (for lack of a better term) as tokushu buraku (特殊部落, ‘special villages/hamlets’). While former status barely affected other members of Japanese society, the burakumin faced discrimination in employment, marriage, education and in many other areas.

Discrimination: Present (An Introduction)

Anyone with ties to the buraku, be they current residents, those that have ‘passed’ out of them and into non-buraku communities, or even the children of the latter group, tend to keep their heritage quiet. Despite the fact that discrimination against them is generally less rampant today, in the south of Japan, particularly in the Kansai region, the burakumin and their ancestors are still ostracised. Continued discrimination has kept them typically in the lower brackets of socio-economic status, and ‘marrying into the buraku‘ is forbidden by a number of parents. Buraku are still largely consist of the areas where eta used to live, and modern-day discrimination occurs largely on this basis. Even people without hereditary ties to the eta or burakumin can be victims of discrimination simply for living in the buraku.

The Activists

In 1922, the first non-governmental organisation concerned with the plight of the burakumin was created in Kyoto. Named the National Levelers Association (Zenkoku Suiheisha, 全国水平社), its founding assembly declared:

“Tokushu Burakumin throughout the country: Unite!

“Long-suffering brothers! Over the past half century, the movements on our behalf by so many people and in such varied ways have yielded no appreciable results. This failure is the punishment we have incurred for permitting ourselves as well as others to debase our own human dignity. Previous movements, though seemingly motivated by compassion, actually corrupted many of our brothers. Thus, it is imperative that we now organize a new collective movement to emancipate ourselves by promoting respect for human dignity.

“Brothers! Our ancestors pursued and practiced freedom and equality. They were the victims of base, contemptible class policies and they were the manly martyrs of industry. As a reward for skinning animals, they were stripped of their own living flesh; in return for tearing out the hearts of animals, their own warm human hearts were ripped apart. They were even spat upon with ridicule. Yet, all through these cursed nightmares, their human pride ran deep in their blood. Now, the time has come when we human beings, pulsing with this blood, are soon to regain our divine dignity. The time has come for the victims to throw off their stigma. The time has come for the blessing of the martyrs’ crown of thorns.

“The time has come when we can be proud of being Eta.

“We must never again shame our ancestors and profane humanity through servile words and cowardly deeds. We, who know just how cold human society can be, who know what it is to be pitied, do fervently seek and adore the warmth and light of human life from deep within our hearts.

“Thus is the Suiheisha born.

“Let there be warmth in human society, let there be light in all human beings.

“March 3, 1922”

A number of the leading figures of this group were recruited into the military, forcing the group to disband in 1942. It was replaced in 1946 by a new group, the National Buraku Liberation Committee (Buraku Kaihou Zenkoku Iinkai, 部落解放全国委員会), formed by surviving members of the Suiheisha. In 1955, it was renamed the Buraku Liberation League (BLL) (Buraku Kaihou Doumei, 部落解放同盟) and survives to the present day.

In 1953, the National Federation of Dowa Educators’ Associations (Zendokyo) (commonly Zendoukyou, 全同教, but in full Zenkoku Douwa Kyouiku Kenkyuu Kyougikai , 全国同和教育研究協議会) was founded with support from the BLL. Educators from Kansai came together to develop a broad reform agenda to fight discrimination against the burakumin in the school system. It “has consistently believed that it should learn from the reality of discrimination and build educational practices that will assure a better life and future for all Japanese children. … It is not enough for students to learn about Buraku issues. It is vital that they experience discrimination themselves in order to deepen their own understanding of it; they ultimately benefit, as they will acquire a broad perspective of humanity, open and less prejudiced attitudes, capacity to empathize with others, and self-identity.”

The other major group campaigning for burakumin rights was the All Japan Federation of Buraku Liberation Movements (commonly Zenkairen, 全解連, but in full Zenkoku Buraku Kaihou Undou Rengōkai, 全国部落解放運動連合会), formed after a purge of the BLL following a leadership decision to exclude non-BLL members from public subsidy payments (which would exclude large numbers of burakumin). Those that left began the Buraku Liberation League Normalization National Liaison Conference (commonly Seijoukaren, 正常化連, but in full Buraku Kaihou Doumei Seijouka Zenkoku Renraku Kaigi, 部落解放同盟正常化全国連絡会議) in 1970, which became the Zenkairen in 1976 (quite probably to distinguish itself from the BLL). The group had ties to the Japanese Communist Party (JCP, Nihon Kyousan-tou, 日本共産党) in contrast to the BLL’s ties to the now defunct Japanese Socialist Party (JSP, Nihon Shakai-tou, 日本社会党). “The Zenkairen promotes social integration of Buraku people with other oppressed people, the independence of Buraku people, and the cooperation of Buraku people with the neighboring communities under the ‘Integration Theory’ [(kokumin yuugouron, 国民融合論)].” In 2004, the group disbanded having announced that “the buraku issue has basically been resolved”.

Despite this, the BLL continues its work, along with International Movement Against Discrimination and Racism (IMADR). Much like the efforts described by David Leheny in Think Global, Fear Local, the BLL is appealing to international norms to solve local problems. The BLL even appealed to the UN for United Nations Non-Governmental Organisation status, essentially a form of legitimisation in the international community. Although the Zenkairen attempted to derail this application, and indeed succeeded, the IMADR is now a consultant to UNESCO (United Nations Economic and Social Council).

The Politics and Legislation

The need to combat discrimination against burakumin reached a period of political awareness in 1960, leading to the 1965 report ‘Fundamental Measures for the Solution of Social and Economic Problems of Buraku Areas’. This report, authorised by Prime Minister Eisaku Sato, detailed the extent of the discrimination and the failure of the government to tackle the problem.

Following the recommendations of the report, a number of Special Measures Laws were drafted. The first, the 1969 Law on Special Measures for Dowa Projects (Douwa Taisaku Jigyou Tokubetsu Sochi Hou, 同和対策事業特別措置法 – I was unable to find the kanji in any English language sources, so consider this an addition to the literature) gave “broad authority for governmental action while mandating virtually nothing. [It created] no legal duties on the part of government agencies and no new legal rights for individuals, either in the form of private causes of action against other individuals or administrative causes of action against public entities.”

Even without mandating action, thirteen years after the implementation of the first Special Measures Law, funding to buraku development projects increased hundredfold on the previous sixteen years. It allowed “autonomous local bodies (most often local branches of the BLL) to improve houses and roads, give scholarships, reduce taxes for small to medium buraku businesses, offer loans at low interest rates, and establish enlightenment programs such as publications for the parent-teacher association.” In 2002, the government terminated the law believing the buraku situation to be improved to the stage where common law can handle it.

The second Special Measures Law was entitled the Law on Special Measures for Regional Improvement (Chiiki Kaizen Taisaku Tokubetsu Sochi Hou, 地域改善対策特別措置法) and enacted for five years from 1982. This was further funding for buraku development, despite not referring explicitly to dowa projects. Controversially, this law was only open to recognised dowa chiku (同和地区, ‘dowa districts’), closing the door for financial aid to buraku who had not been recognised.

The third Special Measures Law continued on from the 1982 law. Enacted for five years, from 1987 to 1992, it was then extended until 1997. The Law Concerning Special Government Financial Measures for Regional Improvement Special Projects (Chiiki Kaizen Taisaku Tokutei Jigyou ni Kakaru Kuni no Zaiseijou no Tokubetsu Sochi ni Kansuru Houritsu, 地域改善対策特定事業に係る国の財政上の特別措置に関する法律) was then amended and extended in part for up to another five year. Again, it is not presented in the context of the buraku mondai, and even excludes areas improved in the previous Special Measures Laws.

One area of change brought about by the 1987 law was to provide loans to secondary education burakumin students instead of the previous grants. Dowa education (dowa kyouiku, 同和教育) is a critical issue for central and local governments and the NGOs involved in the dowa process. They are attempting to combat the discrimination against burakumin by schools, their poor academic performance and their lack of self-esteem. Progress has largely been in the hands of the prefectural governments (kenchou, 県庁) who have proceeded with dowa education onwards from the 1947 Fundamental Law of Education’s (kyouiku kihonhou, 教育基本法) promulgation in 1947. Wakayama prefecture (wakayama-ken, 和歌山県) and Hyogo prefecture (hyougo-ken, 兵庫県) established guidelines for dowa education in those years, and various cities and prefectures have followed.

Discrimination: Present (Redux)

Despite several local and central government policies which have stopped the discriminate listing of buraku, discrimination against the burakumin is still pervasive. In can be seen in defamatory graffiti and posters in cities and throughout the Internet on Japanese language forums (BBS). A 2000 survey by Osaka kencho revealed that 20 per cent of non-burakumin were still reluctant to accepting a marriage with a burakumin and that 40 per cent did not want to live in a buraku. In 1975, it was revealed directories of buraku communities in the hands of private detectives for sale to employers or prospective spouses. These directories are still available if one knows where to look.

Only Osaka, Fukuoka, Kumamoto, Tokushima, Kagawa and Tottori prefectures have legislated against discrimination by employers, and no national government legislation exists against it.

According to a recent survey, 78 per cent of the population of Osaka indicated that they would see a marriage with Buraku people as problematic. Discouragement of marriages is a major obstacle to the integration of Buraku people into the rest of the Japanese society.

In Kyoto prefecture, as reported by Dr. Doudou Diène (the UN Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance) in 2006, the rate of children going to high schools 20 per cent lower amongst burakumin.

Dr. Diène examined Nishinari district in Osaka prefecture, which he called “a special case” due to the amount of mixing in the buraku: over 50% of the people living there were not born there. A 2000 survey discovered that “one household out of five needs income subsidies, the level of schooling is very low (the majority of the elderly residents only completed compulsory education), only 20 per cent of the inhabitants use computers and 10 per cent the internet, which is much lower than the national averages (respectively, 38.6% and 28.9% ), 20 per cent of the houses are insalubrious, 30 per cent of the inhabitants feel useless, and 17.4 per cent were victims of discrimination in relation to marriage. Among young people aged between 15 and 29.17 per cent are unemployed. The elders have extremely low revenues and serious heath problems, 11 per cent of the inhabitants are disabled and only 19 per cent of these people work. … 50 per cent of the inhabitants hesitate to declare their residence.”

Women in the buraku “suffer from double discrimination: as buraku[min], but also as women both outside and inside their community. Some buraku representatives recognized that women are still far from having the same place as man within the buraku community, and that an important effort is required.”

Vicious Cycle

As with many minorities, the burakumin are often seen to comprise art of society’s criminality. As with foreigners, particularly the zainichi Koreans and Chinese, the burakumin are often easy prey for scapegoating. One particular case held up by IMADR is the so-called ‘Sayama Case’, which they summarise on their website:

There are inter-related issues here, one is the efficacy of the koban (call box) system, and Japan’s police in general, secondly is the deficiencies of the legal system (particularly forced confessions), and finally it is the presentation of burakumin as fair game.

Not helping matters is the links between the buraku and the yakuza. It is part of a vicious cycle. The discrimination against burakumin places socio-economic hardships upon them, that as many people might guess makes them fertile grounds for gang recruiting. The situation was a lot worse prior to the Special Measures Laws (perhaps reflected in the yakuza‘s growing interest in the bosozoku following the laws), but continuing discrimination will always aid organised criminals.

Furthermore, yakuza groups have been keen to benefit from the dowa policies. Kunihiko Konishi is a case in point. He was head of an Osaka-based welfare organisation, the Asuka-kai, as well as head of the local BLL chapter. Yet he was also involved with the Yamaguchi-gumi, the top yakuza organisation in Japan. The Asuka-kai received contracts and money for road and building projects as part of a dowa affirmative action policy. Konishi embezzled money and benefited from the abnormal bidding procedures for dowa projects. He was also linked, quite firmly, to the yakuza for many years. In 1985, Yamaguchi-gumi kumicho (gang leader) Masahisa Takenaka was gunned down having visited his mistress in an apartment complex. The apartment was in Konishi’s name and Takenaka was known to all those in the apartment block as ‘Kunihiko Konishi’. The real Konishi, arrested in 2006, was known by many as have strong ties to the yakuza. It is believed that the money diverted from the loans to Asuka-kai was, in part, directed to yakuza groups. Although Konishi might be taken to be an extreme case, he is not the only suspected yakuza in the BLL, it is unsurprising that the disenfranchised burakumin were a firm part of the organised crime scene, and perhaps this cycle is still rolling.

Brief Comparisons

By far the most common comparison made to the burakumin is the ‘untouchables’ of India, indeed, I made that comparison at the start of this post. Both groups were involved with the religiously ‘dirty’ jobs, particularly the leather industry, and both were part of a regulated caste system that governed (and indeed still affects) their lives.

Even closer to home for Japan, Korea has its own group of ‘untouchables’: the Paekchong. Korea had both sides of the eta-hinin, called hwachae and chaein respectively. The hwachae were those who worked with animal carcasses, and the chaein were entertainers, prostitutes and minstrels. Paekchong now refers to the hwachae, just as burakumin refers to eta. They too still suffer discrimination for the careers of their ancestors.

The Way Forward

For the Japanese government, the way forward is better education. The affirmative action policies have now been largely disengaged. This is indeed a good way to go ahead, but it can only go so far. Educating the burakumin themselves and Japanese in general about the history of the eta will go some way to laying the foundations for a better future. After all, the burakumin are ethnically Japanese… if Japan cannot reconcile its caste system’s legacy, then what are the chances of it accepting the Ainu and ethnic Okinawans, zainichi Asians, and growing numbers of foreigners of all colours?

Familiarity is also a tool to be employed. In Dr. Diène’s study of Nishinari, Osaka, he found that the district leaders were aware that neighbouring districts are much less discriminating than the ones that are far away. Therefore, the district is establishing links between various communities, promoting mutual knowledge. However, one might also suggest that those districts closest to the buraku might also be discriminated against (perhaps inhabited by zainichi, for instance).

For the Buraku Liberation and Human Rights Research Institute (BLHRRI), the class system of the Edo period excluded the eta–hinin to the extent that they were not part of the identity constructed collectively in Japan. The challenge is to reconcile that identity with reality. That might also go some way towards solving the other problems of discrimination in Japanese society.

See it For Yourself

8 Comments

This election cycle is one of the first where Buraku issues are being discussed openly, though it’s really taken political issues to force them to that point, and only where that’s been a flare-up – in Osaka.

This is due to the continuing fallout from the Konishi and the Asukakai affair, right?

Very interesting post Shingen! I appreciate all the work you put into it.

I’ve asked my wife (Japanese) about the Burakumin but she didn’t know much about the subject. However, she did say that in high school she was taught that this class of people was “created” to elevate the merchants and common-folks from the bottom ranks.

By the way, thanks for already linking my new blog (canapan.blogspot.com) to your site. I look forward to your comments.

Regards,

No problem, I look forward to commenting ;)

I did a word count, this post was 4,000 words long… larger than my normal essays!

My girlfriend, from Hokkaido, had a similar response. She did not believe that the discrimination was ongoing, although had I have done a post about the Ainu she would have been much more aware. I believe that people from Osaka would probably be most aware of the buraku mondai.

There were a couple of things I missed, so I’d like to put them down now…

1. At Yasukuni, while the Koreans and Taiwanese fighting for the Imperial Army are enshrined there, burakumin are not.

2. The discrimination is evident in the political elite, take for instance Taro Aso’s comment that I quoted in a previous post:

I live in Kobe, asked my girlfriend about this issue and she seemed very uncomfortable talking about it. She’s from a wealthy family and went to private school. She said her parents never taught her about this and the subject is never broached in private schools. She found out from her ex’s parents (at the age of 28!) and her parents were very upset when she asked them about it. Not because they were ashamed of the discrimination and history, but simply because they wanted to keep her from knowing about it at all. Furthermore, they would actively check on any potential spouse’s background.

Also asked a 65year old dentist student of mine his opinion. He said that although the affirmative action policies in Kansai meant the geographical areas were more clearly identifiable, in Tokyo the problem still exists and anyone over 40 or so is aware of the Buraku areas and likely to have negative opinions and/or engage in discrimination

Thanks for the comment, Seth.

I’ve not really discussed the Buraku issue with my students, but perhaps I should give it a go with the more open ones.

As I stated in a later blog post (Google Earth vs the Burakumin), I don’t think the forced ignorance approach is a good one by any means. Only by being open about this history and these people can we heal the wounds of discrimination… the problem is that too many people are seemingly not willing to engage in that level of introspection.

Absolutely, there does tend to be a general attitude of ignorance towards any social issues in Japan. Sweeping it under the carpet/ burying their heads in the sand seems to be part of the national psyche (without wanting to generalise too much, of course there are exceptions). I’ve even had students deny problems exist and actually get quite offended when I attempted to discuss topics such as increasing alcoholism and obesity, even though my statements were backed up by hard evidence. They often seem to want to believe Japan is perfect and can take any mention of problematic areas of Japanese society as a personal attack. Tread carefully! I’m sure you know your students well enough to judge though.

I found your article very informative and well-wriiten. Congratulations on exposing this human rights problem. I lived in Japan for three years and researched the topic for a Kansai Scene magazine article I wrote on the buraku. You might like to have a look at it here:

http://www.bretthetherington.net/default.aspx?pageId=116

4 Trackbacks/Pingbacks

[…] info y fuentes Burakumin (Inglés) Muy interesante por cierto. La sociedad japonesa (Gunkan) Koseki […]

[…] Saigo Takamori and Kido Takayoshi. Okubo, as Finance Minister, ended discrimination against the eta-hinin. He was part of the very important around-the-world Iwakura mission to renegotiate unequal treaties […]

[…] 1.2 million of them today) and Dalits in South Asia. The graphic chart on the right was taken from Abduction Politics, a blog with an extensive post on the […]

{Hurricane Ridge Wa … Hurricane Irene Coverage … | Hurricane Predictions For 2011 … Hurricane Zip Code … Hurricane Quick Facts … | Hurricane Irene … Hurricane 6.5 Catamaran … | Hurricane Xl 80 Reel … Hurricane Irene Queens … Hurrica…

Hurricane 551 Holosight … Hurricane 2008 … Hurricane Irene Images ……